Pharmacy reimbursement models: how laws affect generic payment

marras, 16 2025

marras, 16 2025

When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you might think it’s just a cheaper version of the brand-name drug. But behind that simple swap is a web of laws, payment rules, and financial incentives that shape exactly how much you pay - and how much the pharmacy gets paid. In the United States, generic drug reimbursement isn’t just about cost savings. It’s a system built by federal and state laws that determine who gets paid what, when, and under what conditions. And those rules directly impact whether you get the drug you need, at a price you can afford.

How generic drugs got their place in the system

The modern foundation for generic drug access was laid in 1984 with the Hatch-Waxman Act. This law created a faster, cheaper path for generic manufacturers to get FDA approval without repeating expensive clinical trials. In return, brand-name drug makers got extra patent protection to make up for time lost during FDA review. The goal? More competition. Lower prices. More access. Today, nearly 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are for generic drugs. Yet they make up only about 23% of total drug spending. That’s the power of substitution - when a pharmacist swaps a brand-name drug for its generic equivalent, it saves billions every year. But here’s the catch: just because a generic is cheaper doesn’t mean the pharmacy gets paid enough to cover its costs.Two main ways pharmacies get paid for generics

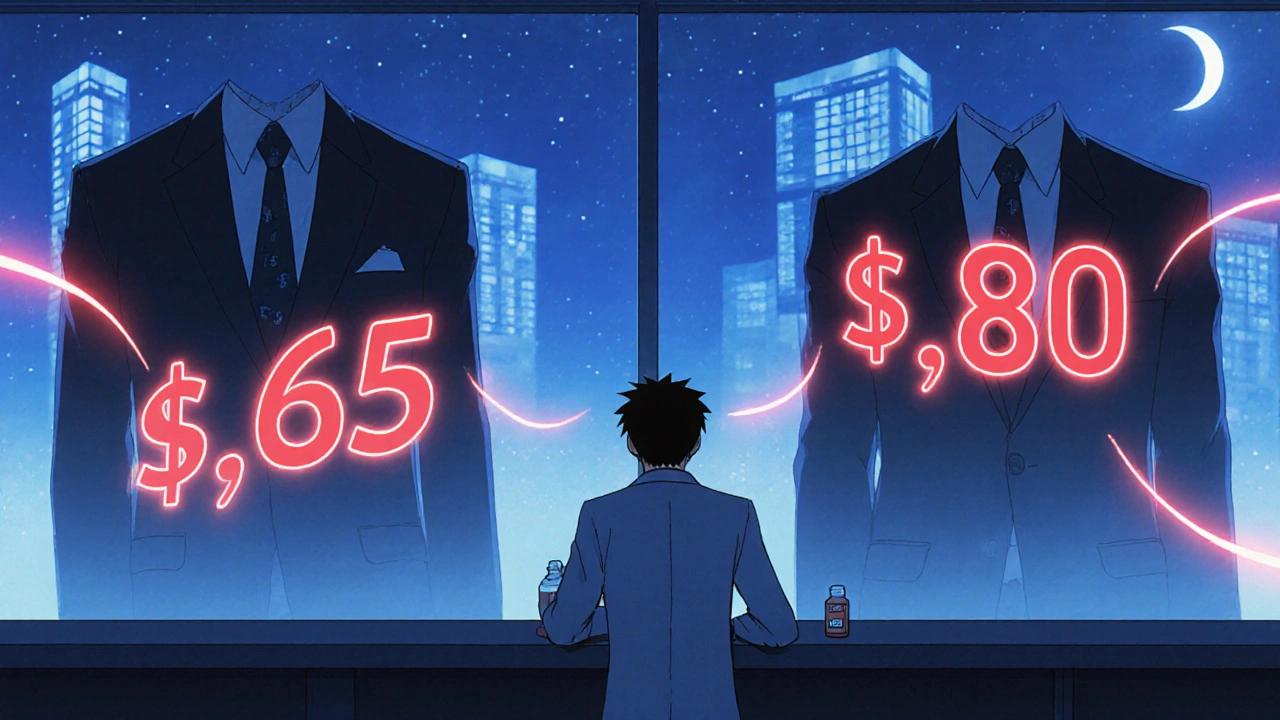

There are two big reimbursement models for generic drugs: Average Wholesale Price (AWP) and Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC). AWP used to be the standard. It’s a list price set by manufacturers, often inflated, and pharmacies got paid a percentage off that number. But because AWP didn’t reflect real-world costs, it led to overpayments and fraud. Today, most payers - including Medicare and Medicaid - have moved away from AWP for generics. Enter MAC. This is now the dominant model. MAC sets a fixed maximum payment per pill or capsule based on what pharmacies actually pay for the generic drug. If the pharmacy buys the generic for $0.50, and the MAC is $0.60, they get $0.60. But if the generic costs $0.70? The pharmacy eats the $0.10 loss. This system sounds fair - until you realize that MAC lists are updated infrequently. A pharmacy might buy a generic for $0.80, but the MAC hasn’t changed in six months and is still set at $0.65. That’s a $0.15 loss per prescription. Multiply that by hundreds of prescriptions a day, and it’s not just a loss - it’s a threat to survival, especially for small, independent pharmacies.

Who controls the rules? PBMs and state laws

Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) - companies like CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRX - are the hidden architects of reimbursement. They negotiate with drug makers, set MAC lists, and contract with pharmacies. They make money in two ways: by taking a cut of rebates from manufacturers and by keeping the difference between what insurers pay and what pharmacies get paid - known as “spread pricing.” For years, PBMs used “gag clauses” to stop pharmacists from telling patients: “This drug is cheaper if you pay cash.” That changed in 2018 when federal law banned the practice. But the financial pressure remains. In 2023, the average profit margin on generic drugs for independent pharmacies was just 1.4%. In 2018, it was 3.2%. That’s a 58% drop in just five years. States have started pushing back. As of 2023, 44 states passed laws to regulate PBMs - requiring transparency in MAC pricing, banning spread pricing, and forcing PBMs to pay pharmacies fairly. But these laws vary wildly. In one state, a pharmacy might get reimbursed based on real-time wholesale prices. In another, they’re stuck with a MAC list updated once a year.Medicare Part D and the $2 Drug List Model

Medicare Part D covers over 50 million seniors and people with disabilities. It’s a patchwork of private plans with different formularies, copays, and rules. Generics are usually on lower tiers - meaning lower out-of-pocket costs for patients. But not always. In 2022, 28% of Part D plans required prior authorization just to fill a generic drug. That’s a bureaucratic hurdle that delays care. Some plans even make patients pay more for a generic if it’s not on their “preferred” list. That’s why CMS introduced the Medicare $2 Drug List Model in 2025. This voluntary program targets about 100-150 low-cost, high-use generic drugs - like metformin, lisinopril, or atorvastatin - and caps the patient copay at $2. The goal? Reduce confusion, improve adherence, and cut administrative waste. To qualify, a drug must be clinically important, widely used by Medicare beneficiaries, and available from multiple manufacturers. The model is modeled after what grocery chains like Walmart and Costco already do: fixed, ultra-low prices on essential generics. But unlike those stores, Medicare’s model forces plans to adopt it - and pay pharmacies fairly for dispensing.

What’s broken - and what’s changing

The system still has major flaws. “Authorized generics” - where brand-name companies release their own generic version - suppress competition. Instead of letting new manufacturers enter the market, they block them with a cheaper version of their own drug. That keeps prices higher than they should be. Then there’s the “donut hole” - the coverage gap in Medicare Part D. Even though the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 capped out-of-pocket costs at $2,000 starting in 2025, many seniors still face high deductibles and unpredictable costs for generics. Independent pharmacies are on the edge. With margins shrinking, some are closing. Others are turning to cash-only sales for generics - bypassing insurance entirely. That’s not a solution. It’s a symptom of a broken system. But change is coming. The Federal Trade Commission is cracking down on “pay-for-delay” deals - where brand-name companies pay generic makers to delay launching their drugs. And new state laws are forcing PBMs to disclose their pricing rules.What this means for patients

You don’t need to understand MAC lists or PBM spreads. But you do need to know this: your pharmacy can’t always tell you the real price of your generic drug because the reimbursement system hides it. That’s why it’s smart to ask:- “Is this drug on my plan’s preferred list?”

- “Can I pay cash instead of using insurance?”

- “Is there a cheaper generic version available?”

Carmesa Rojas

marraskuu 18, 2025 AT 07:42It's wild how we treat medicine like a commodity when it's literally about life and death. The whole MAC system feels like a game of musical chairs where the pharmacy always loses the seat.

Tuomo Pekkanen

marraskuu 18, 2025 AT 14:59From a reimbursement standpoint, the shift from AWP to MAC was necessary but poorly executed. MAC lists need real-time indexing tied to wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) data, not quarterly snapshots. Otherwise, you're incentivizing pharmacy closures instead of generic adoption. The PBM spread pricing model is the real tax on access.

And don't get me started on authorized generics - it's anticompetitive by design. Brand manufacturers aren't innovating; they're just gaming the Hatch-Waxman framework to delay true generic entry. FTC needs to enforce Rule 10b-5 here.

The $2 Drug List model is the first federal step in the right direction. If CMS can enforce transparent, volume-based reimbursement tied to actual dispensing costs, we might finally align incentives. Pharmacies aren't charities - they're essential infrastructure.

State-level PBM regulation is fragmented, but it's creating a policy lab. Minnesota's transparency laws and California's MAC audit requirements are models worth scaling nationally.

Patients need to know: paying cash often beats insurance for generics. The system is so broken, the most rational financial move is to bypass it entirely.

Pinja Sanaksenaho

marraskuu 19, 2025 AT 08:24i think the whole thing is just a big scam tbh. pharmacies are gettin ripped off but also like… why do we even need all these middlemen? pBms are just glorified bill collectors with fancy titles. also the $2 thing sounds nice but i bet they’ll find a way to screw it up. also typo? i think i meant ‘screw’ not ‘screw’ wait no i meant it.

Frida G

marraskuu 19, 2025 AT 10:30Oh please. You're all just romanticizing the corner pharmacy. Let's be real - most generic drugs are manufactured in China or India. The idea that a small Finnish pharmacy is some heroic guardian of public health is delusional. The system works because it's efficient. Stop pretending this is about morality.

Jill Ståhle

marraskuu 20, 2025 AT 06:20As someone who's worked in Nordic pharmaceutical logistics, I can confirm: the U.S. model is a mess. But here's what's missing in your analysis - the role of formulary tiering. In Sweden, generics are automatically preferred, no prior auth needed. The real issue isn't reimbursement - it's clinical inertia. Doctors still prescribe brand names out of habit.

And yes, PBMs are predatory. But the solution isn't more regulation - it's public procurement. Sweden negotiates drug prices nationally. Why can't the U.S. do that for the top 100 generics?

Alex Holm

marraskuu 20, 2025 AT 09:18This whole post is just liberal whining. Pharmacies make money on prescriptions. If they can't handle the math, they shouldn't be in business. Americans are too soft. In Sweden, we don't cry about $0.15 losses. We just work harder. And stop blaming PBMs - they're just doing their job. The problem is patients who think medicine should be free.

Tiina Vehviläinen

marraskuu 20, 2025 AT 09:39Why do we even care? It's just pills. People take them anyway. Let the market sort it out.

Hjalmar Heimbürger

marraskuu 20, 2025 AT 14:59There's a real human cost here. I've seen pharmacists work 12-hour days just to keep their doors open, barely breaking even. The $2 Drug List could be a lifeline - if it's implemented with real oversight. We need to stop treating healthcare like a spreadsheet and remember it's about people.

And yes, paying cash is often smarter. I do it for my dad's blood pressure med. Saves $18 a month. That's a pizza night.

Johanna Markkanen

marraskuu 21, 2025 AT 04:09The MAC system’s failure to reflect WAC is a structural flaw. Tiered reimbursement based on therapeutic equivalence classes would reduce arbitrage. Also, PBM gag clauses may be banned, but de facto suppression via formulary exclusion persists.

Elina Sports

marraskuu 21, 2025 AT 11:55So basically, the system is designed so pharmacies lose money on the very thing that saves everyone money? Classic. I mean… congrats, capitalism. You turned saving lives into a loss leader.

Also, I just asked my pharmacist if I could pay cash for my metformin. She laughed and said, 'Honey, it's $4. Insurance would cost you $22.'

And yes, I'm now the neighborhood pharmacy activist. Who knew?

Leif Majeres

marraskuu 22, 2025 AT 07:58Sweden doesn't have PBMs. We have the Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency (TLV) that negotiates national prices. No spreads. No gag clauses. Just fair reimbursement. The U.S. could adopt this tomorrow - if it wanted to.

And the $2 model? Brilliant. It's what Costco does. Why is a government program copying a warehouse store? Because the private system failed.

JOHAN MATA

marraskuu 22, 2025 AT 13:14Guys. I just checked my local CVS. They're charging $3 for lisinopril cash. Insurance? $19. I told them I was going to the pharmacy down the street. They gave me a coupon. The system is broken, but people are finding workarounds. That’s not failure - that’s adaptation.